Hosinsul on Gradings: Technique, Safety, and Fair Assessment

By Roy Rolstad

One of the recurring discussions in Taekwon-Do, especially among experienced instructors, is how Hosinsul (self-defence) should be conducted and assessed during gradings. The debate is healthy, necessary, and reflects a deeper question:

What are we actually testing when we examine self-defence?

Recently, this discussion resurfaced in a conversation with a respected Taekwon-Do colleague. His position was that Hosinsul during grading should be more unpredictable and realistic, possibly involving unfamiliar partners and unscripted attacks, while still being performed “with some control.”

My position, aligned with both long-standing ITF tradition, the principles of ITF Radix, examining law enforcement recruits and law enforcement rerseetification in use of force and selfdefense is different:

A grading is not the place for realism by default. It is the place for clarity, safety, and technical evaluation.

This becomes especially important when gradings are conducted with joint examiner panels and candidates from multiple clubs and instructors, which is often the case at regional and national examinations.

The Purpose of Hosinsul in a Grading Context

In Taekwon-Do, Hosinsul on a grading should have a clearly defined purpose. It exists to give the examiner a structured basis to evaluate whether the candidate demonstrates:

Understanding of fundamental self-defence principles

Technical skill appropriate to age and grade

Balance, coordination, and body control

The ability to apply techniques safely, deliberately, and correctly

Hosinsul at grading is therefore a technical assessment, not a stress test, a fight simulation, or a competition. It is not intended to replicate real violence, and it should not attempt to do so.

This distinction is crucial, particularly in multi-club grading settings, where neither examiner nor candidate can assume shared preparation, terminology, or methodological emphasis.

Why Controlled Conditions Matter, Especially in Joint Gradings

From an examiner’s perspective, the grading environment must allow for equal evaluation across:

Different ages

Different body sizes

Different genders

Different physical and psychological maturity levels

Different club cultures and instructional approaches

In joint gradings, where students may be examined by instructors they have never trained with, controlled and predictable Hosinsul is not merely a preference, but a necessity.

Allowing unpredictable attacks or improvised scenarios in such contexts introduces variables that are unrelated to technical understanding and progression. Instead, they reward factors such as:

Familiarity with a specific instructor’s training philosophy

Personal tolerance for chaos or stress

Physical dominance rather than technical clarity

None of these provide a fair or comparable assessment basis when multiple clubs and examiners are involved.

The Role of the Partner: A Technical Instrument, Not an Opponent

In a grading context, the partner’s role is often misunderstood.

The partner is not there to challenge, surprise, or test emotional resilience. The partner is there to deliver a clear, correct attack that allows the candidate to demonstrate technical understanding.

This is particularly critical in joint panels, where:

Partners may not have trained together previously

Instructors may interpret “realism” differently

Misalignment increases the risk of injury or misjudgment

For this reason, a framework should specify:

A fixed partner

Known attacks

No improvisation or resistance

This does not make Hosinsul artificial, it makes it transparent and assessable.

Known Attacks and Defined Parameters

In my opinion, Hosinsul should be understood as an application of:

Pattern logic

Biomechanics

Distance and positional principles

These elements require attacks that are:

Clearly defined

Appropriate to age and grade

Agreed upon in advance

This shared framework becomes essential when examiners and candidates do not come from the same training environment.

What should intentionally be excluded in joint grading situations:

Surprise attacks

Compound or deceptive attacks

Multiple attackers

These elements may be valuable in training, but they cannot be assumed as common ground during examination.

Technique Over Drama

A frequent grading error is confusing intensity with quality. I have personally done this mistake in the past myself. It may be entertaining for the public but it has nothing to do with the execution of technique.

I want to place emphasis on:

Distance management

Timing

Balance and posture

Structural integrity

Controlled resolution

In joint examinations, dramatic or highly individual expressions of Hosinsul often lead to inconsistent scoring, not because the techniques are wrong, but because they are interpreted differently by different examiners.

Clear structure removes ambiguity.

Safety Is Not a Compromise, It Is a Shared Responsibility

In any grading, especially one involving multiple clubs and examiners, safety must override stylistic preference.

Controlled tempo, stopped strikes, and safe execution of locks and throws are non-negotiable. A grading environment must protect:

Candidates

Partners

Examiners

The credibility of the system itself

An examination that relies on informal assumptions about “how we usually do it in our club” is fragile and unsafe.

Age, Grade, and Contextual Adaptation

We should support differentiated expectations:

Children and youth

Simple techniques

Lower tempo

Emphasis on escape, distance, and control

Adults and higher grades

Greater technical variation

Smoother transitions

Clear tactical reasoning

However, these adaptations must still sit within a shared and communicated framework when assessments are conducted across clubs.

When a More Realistic Approach Can Be Appropriate

There are situations where a more realistic or dynamic Hosinsul approach may be appropriate during a test—but only under clearly defined conditions:

The examiner panel and instructors share a common understanding of the approach

The candidates have trained specifically for this format

The parameters, intensity, and safety expectations are clearly communicated in advance

All participants are prepared, technically, physically, and mentally

In other words, realism in testing must be intentional and consensual, not improvised or assumed.

This type of approach is far more suitable for:

Advanced adult examinations

Club-specific gradings

Instructor certifications

Specialized self-defence assessments

It should never be introduced ad hoc in a joint grading environment.

Where Realism Primarily Belongs

ITF Radix strongly emphasizes that realistic self-defence training is essential, but its primary home is in:

Regular training

Dedicated self-defence sessions

Seminars and courses

Adult classes with progressive exposure

These environments allow:

Gradual stress adaptation

Instructor oversight

Informed consent

Proper recovery and reflection

Trying to test realism without this preparation undermines both safety and learning.

A Clear Boundary Creates Better Training and Fairer Gradings

One of the most important insights from long-term teaching experience is this:

The clearer the boundary between grading and training, the stronger both become.

Standardised Hosinsul at grading:

Protects students across clubs

Supports examiner consistency

Reduces unnecessary conflict

Preserves trust in the system

At the same time, instructors remain free, and encouraged, to explore realism deeply and responsibly in training.

Conclusion

Hosinsul at grading is not designed to simulate violence. It is designed to evaluate understanding.

This is especially critical when examinations involve:

Joint examiner panels

Candidates from multiple clubs

Different instructional backgrounds

By keeping Hosinsul:

Structured

Controlled

Predictable

Clearly communicated

Adapted to age and grade

we ensure that grading remains what it is meant to be:

A fair, safe, and meaningful assessment of technical progression.

Realism has great value, but only when everyone involved is prepared for it.

Roy Rolstad

ITF Radix

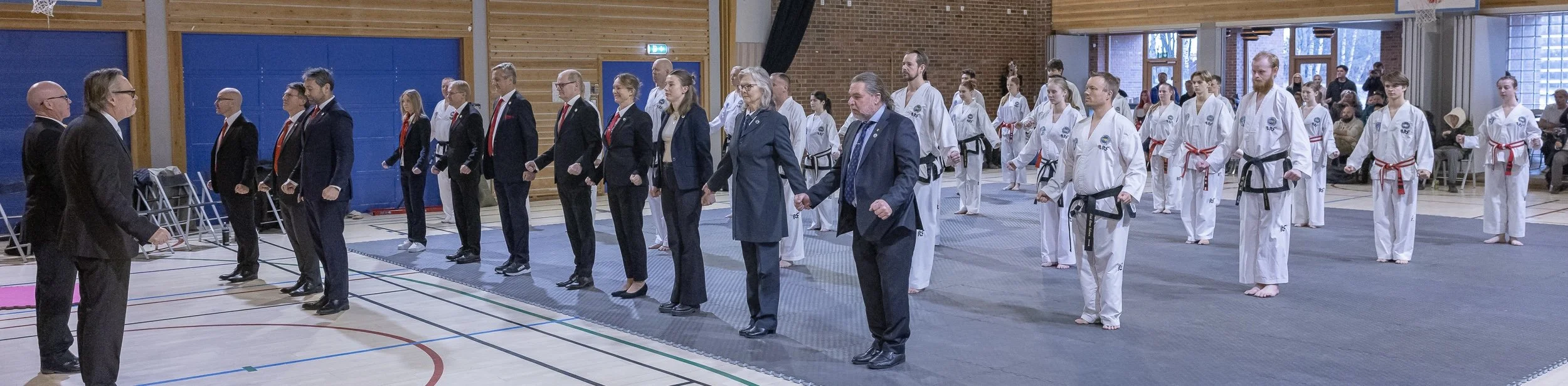

Photo: Raimon Bjørndalen