From Hanja to Hangul: Roots and Branches of ITF Radix

By Roy Rolstad, VI Dan, ITF Taekwon-Do

When we look at the history of Korea, language is a mirror of identity, culture, and philosophy. In Taekwon-Do, where words like Bon (본, 本), meaning “root, origin, or essence”, carry layers of meaning, we see how language and martial practice intertwine.

Today, in ITF Radix, we draw on both the past and the present: the deep roots of Hanja (Chinese characters used in Korea for over a thousand years) and the unique brilliance of Hangul (the Korean alphabet created in the 15th century). Learning a little bit about these two writing systems opens a door into the very philosophy behind ITF Radix: to return to the root, and from there, to grow.

The Legacy of Hanja, The Root Characters

Before the invention of Hangul, the Korean language was written almost exclusively with Hanja (漢字). These Chinese characters carried not only sounds but also ideas. Each sign is a symbol of concept and philosophy. For example:

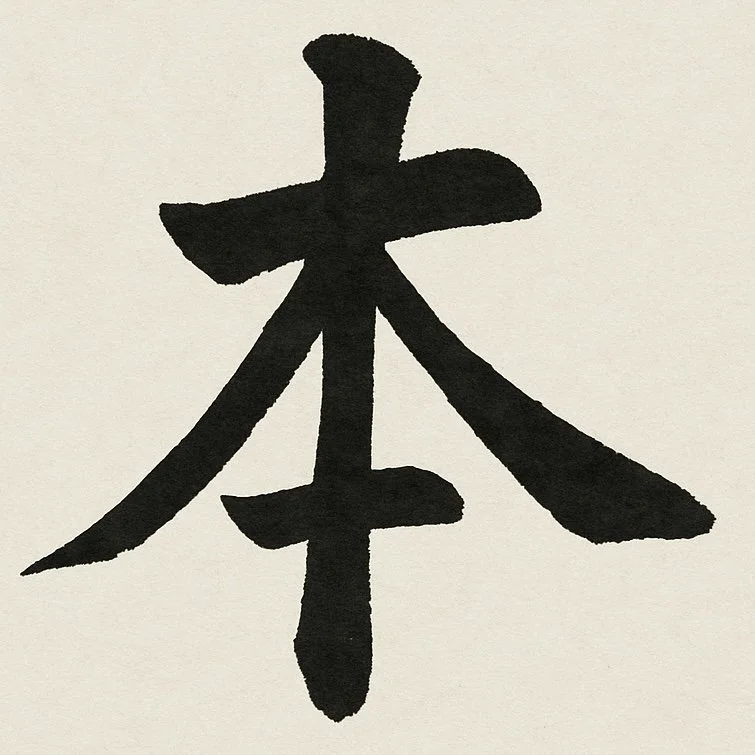

本 (bon) = root, origin, essence.

道 (do) = the Way, the path, the guiding principle.

武 (mu) = martial, to stop conflict.

These characters are not abstract; they are visual metaphors. 本 shows a tree 木 with an extra stroke at the base, symbolizing its root. In each hanja character the meaning grows out of imagery.

In Taekwon-Do, General Choi Hong Hi borrowed from this cultural and philosophical heritage. The names of the patterns, the terminology of the art, and the moral guidebook are deeply tied to Hanja concepts. To study Hanja is to glimpse the philosophical soil from which Taekwon-Do grew.

Hanja character describes “Root” in English, or “Radix” in Latin.

The Brilliance of Hangul, The People’s Script

In the 15th century, King Sejong the Great changed the course of Korean history by creating the Hangul alphabet (한글). Unlike Hanja, which required years of study, Hangul was designed to be simple, scientific, and accessible. King Sejong famously declared:

“A wise man can learn it in a morning, a fool in ten days.”

Hangul was a revolution. It gave voice to the common people, who no longer had to rely on the elite knowledge of Chinese characters to read or write. It was a alphabet, and it was an act of cultural independence, a declaration that Korea had its own way.

In Korean writing the word “Radix”, or “Root” is translated “Bon”

ㅂ (b/p) = initial consonant

ㅗ (o) = vowel

ㄴ (n) = final consonant

When we write bon as 본, we are seeing the bridge between Hanja and Hangul. 본 is the phonetic spelling, while 本 is the philosophical root. Together they show how Korea carried forward its heritage while creating something entirely new.

ITF Radix, Returning to the Root

The word Radix itself means “root” in Latin, and this is not a coincidence. The project exists to explore Taekwon-Do as a complete fighting system by returning to its foundations, the roots that are often hidden beneath the surface of patterns and drills.

Our philosophy is simple:

Learn the pattern to understand its visible form.

Learn the application and uncover its hidden function.

Play and explore variations, test the principles.

Fight to pressure-test, refine, and integrate.

This four-step cycle reflects the same dynamic between Hanja and Hangul. Just as Hanja preserves the root meaning and Hangul makes it accessible, ITF Radix holds the philosophy of Taekwon-Do in balance: the depth of tradition with the practicality of modern training.

When we bow in and practice a pattern, we are moving our bodies, and we stepp into a centuries-old dialogue of symbols, philosophy, and martial wisdom.

By connecting Hanja and Hangul, root and branch, Radix reminds us that every technique has both a visible form and a hidden essence.

In Korean language and in Taekwon-Do alike, the “root” matters. We can think of Hanja as the philosophical foundation, and Hangul as the accessibility to carry it forward.

ITF Radix builds on that dual heritage, digging into the roots of Taekwon-Do so that practitioners today can grow tall and strong in their practice.

When we write 본 (본, 本), we are writing a word, and we are naming a philosophy:

“Return to the root, grow from the essence, and let the art live fully, in practice, in play, and in combat.”